May 31. By Mark Washburn. Christopher Palmiter was found guilty Friday of failing to notify authorities of the disappearance of his stepdaughter Madalina Cojocari, a story that has attracted national attention in the 18 months since she vanished from her Cornelius home.

Palmiter, who had no previous criminal record, was sentenced to 30 months probation and ordered to pay attorney fees by Superior Court Judge Matthew Osman.

Palmiter

Palmiter showed no emotion during the verdict, remaining stoic as he had throughout the eight-day trial, but smiling in apparent relief as he stood beside his attorney afterward.

“I believe he’s innocent,” said Brandon Roseman, his Charlotte lawyer. “Mr. Palmiter maintains his innocence and appreciates the service of the jury.

Roseman said he has begun the appeal process.

It took jurors less than 30 minutes to reach the verdict. It was delivered by the foreman, a retired Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police sergeant.

D Cojocari

Palmiter has already served eight months in jail in pretrial detention before getting bail in August. His wife, Diana Cojocari, served 17 months on the same charge before pleading guilty last week and being released for time served.

Closing arguments

In closing arguments, Roseman told jurors that Palmiter, 61, had been cruelly manipulated and dominated by Cojocari, 39, a Moldovan woman who befriended him online and eventually married him in 2016, coming to the United States a month before the ceremony on a visa he had arranged for her and her them-4-year-old daughter, Madalina.

He went through the timeline he had elaborately presented in the trial, showing that in the weeks leading up to disclosure of the girl’s disappearance, she had sent him on a long trip to Michigan, told him that she and Madalina were on trips to the mountains, that Madalina was in her room in their Victoria Bay home suffering from illness and sending messages indicating that the two of them were together.

But prosecutor Austin Butler instructed the jury that no amount of befuddlement on Palmiter’s part or fear of a dominating wife excused him from his duty as a parent or guardian from notifying authorities when he didn’t know the 11-year-old’s whereabouts for more than 24 hours.

“If she’s really crazy,” Butler said, “he’s an educated guy … isn’t that more reason he should have contacted police?”

In the end, Butler insisted, all that mattered under the definition of the charge was that he was in a parental role and failed to tell authorities when he began to suspect that Madalina was missing.

The jury went around the room only once, achieving a unanimous guilty verdict.

Palmiter’s defense

The defense introduced an unusual but oddly compelling story: That Palmiter, misled and browbeaten by his wife, actually believed that the girl was still around despite not seeing or talking to her.

From his view, the defense maintained, he worked long hours away from home, was sent on various prolonged errands by his wife and believed she was sometimes out of town with the girl in the late autumn of 2022.

Palmiter’s unusual countenance before the jury spoke in its own way. He was a man with an unwavering serious air, never laughing with others even during the brief moments some amusing courtroom aside occurred.

He sat throughout in a mist of gloom, as though in dread suspense and expectation. He wept on the witness stand when disclosing the failures of his sham marriage and the memory of Madalina.

Throughout, he maintained that he didn’t really know she was gone until he was summoned to Bailey Middle School on Dec. 14, 2022 where his wife had told police that Madalina had mysteriously vanished.

Could he really not have known?

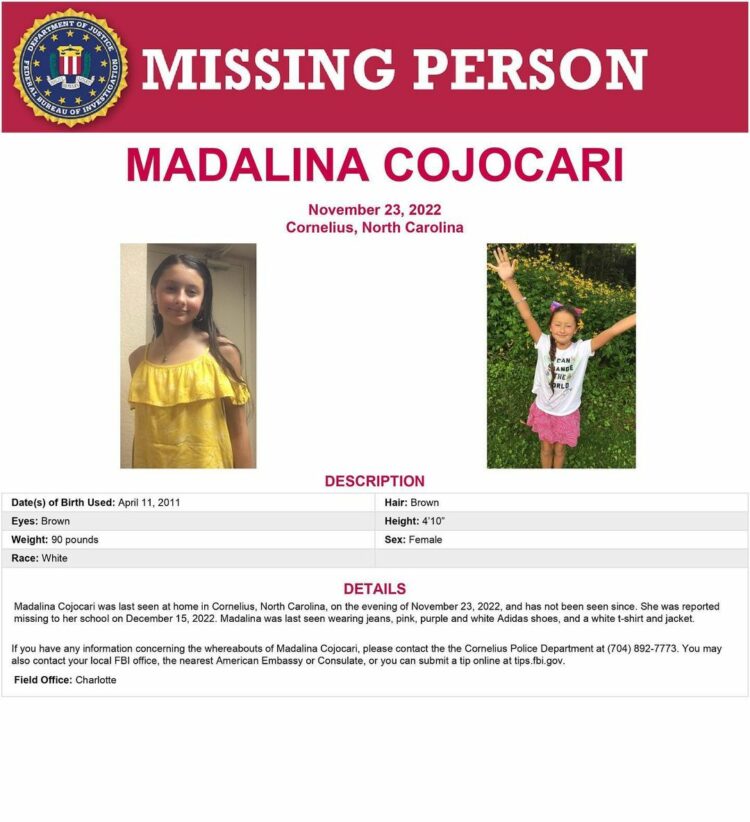

Missing: Madalina Cojocari

A pattern of troubling behavior

To fortify that possibility, the defense has constructed a sketch of Palmiter’s unusual life and manner:

– He hadn’t had a serious romantic interest since college. In his mid-50s, he met a woman from Moldova, an impoverished former Soviet bloc country, through an online site. She said she was a teacher there and they began to explore a relationship.

– After more than a year, he visited her in Moldova. They went to dinners, parks, cultural sites. He said it seemed to be working out.

– He returned some months later and gave her a promise ring, an indication, he said, that they should continue to explore the relationship.

– But they later lost contact. Finally she got back in touch, admitting that she’d gotten pregnant by a local man between his two visits. But if he were still interested, so was she. And he was.

– Later, he proposed and after hiring lawyers to go through a two-year immigration process, she came to the United States on a visa with her toddler daughter. They were married a few weeks later in January 2016, discovering in the process of getting a marriage license that she had misrepresented her age by several years.

– Their marriage was never consummated. Cojocari withheld affection aside from the kiss on special occasions, he said.

– Cojocari grew to be a demanding authority figure in their household and Palmiter seemed to accede to her commands, even when they became extreme. Dave Vermilyea of Kernersville, an automotive engineer, testified that he was a longtime friend of Palmiter’s until Cojocari came into his life.

Once on a trip to Ocracoke, people in their group began snapping pictures of a rainbow above a cloud. Cojocari told them to cease because what they were seeing was an angel getting its crown, and photographs were sacriligious.

He said he finally had to tell her to back off. When asked whether Palmiter might have stepped in, Vermilyea replied, “No way,” shaking his head and wincing.

– After Cojocari told him in the summer of 2022 that Russian president Vladimir Putin and rock star Michael Jackson were stalking her because she had certain Russian nobility titles they coveted, he continued to do her bidding, though he found the plot unlikely. He arranged for Cojocari and Madalina to go to Michigan and hide out for a time from the pursuers with relatives in his large Lansing-centric clan.

– On the day before Thanksgiving 2022, she ordered him out of the blue to drive from Cornelius to Michigan to pick up some clothes she and Madalina left there during their retreat from Putin and Jackson. He complied, packing immediately and starting the 12- to 13-hour trip within minutes. He didn’t see Madalina that morning – Cojocari told him she was asleep upstairs – nor any day afterward.

– After the daylong return trip from Michigan later that weekend, he was unpacking the items she’d requested when she told him to go to the store and buy soft cat food. He complied obediently, going to two stores because the first didn’t have the exact brand she’d specified.

– On the following week, he was unable to work from home because the internet cable had been cut. He made the 90-minute each-way commute to Greensboro. He said he usually got home after Madalina’s bedtime and didn’t see her that week. AT&T reported that when a technician was sent to the home, no one answered the door; Cojocari told him that she and Madalina were out together in town at the time of the appointments.

– Then he said he was told by Cojocari – once with a note stuck to the refrigerator – that she and Madalina were off on short trips to the mountains.

– Whenever he asked where Madalina was during the 17 days, he said, Cojocari would cruelly mock him, parroting his words back at him, asking whether he knew.

– There were repeated instances where Palmiter struggled with a cognitive problem. He admitted that he used his phone to take pictures of things as a memory aid, like notes and lists and even changes in the house.

– Friends and relatives testified that Cojocari was the dominant personality in the marriage. Palmiter told of repeated instances where he sought to appease Cojocari to avoid confrontations.

Relations with wife

Palmiter said Thursday that after Cojocari was released from jail last week after 17 months for her part in failing to report Madalina’s disappearance, he found her sleeping on a porch swing at their home.

He let her come inside and spend the night, then the next day his brother took her to a hotel in Huntersville.

He said he didn’t know that her appearance at their house – her name is also on the deed, he noted – would be a problem, but that he really didn’t want her there. He said they have not been in contact since.

Early search of house

Cornelius detective Gina Patterson, a 21-year veteran of the department, testified Thursday that she went to the Palmiter home after school authorities said Madalina was missing.

Immediately, she noticed the strong odor of cat urine. About a dozen cats lived in the house and Palmiter had already said they were destructive to furniture and relieved themselves at will.

“They were everywhere,” Patterson said.

During the search, a number of Western Union receipts were found, Patterson said. Cojocari had wired a total of $7,000 to relatives in her native Moldova, she said.

Cojocari’s handbag contained about $7,500 in cash, Patterson said.

In the 17 days that Madalina was missing before being reported, Patterson said, Cojocari’s car was detected through law enforcement license-plate scanners in Cornelius, Boone and the Gatlinburg, Tenn., area. She was in a traffic stop by a deputy in Madison County, in the N.C. mountains and seen on security cameras in various places in the highlands. Madalina was never seen with her.

She also said that Palmiter had admitted during a police interview that when he returned from Michigan over Thanksgiving, Cojocari had apparently burned everything in the house with Madalina’s image on it.

Cojocari not called to testify

Cojocari was the unseen witness throughout the trial. Defense attorney Brandon Roseman decided at midday that he would not call her to testify, though she had been standing by in the courthouse for two days in response to a subpoena he’d issued.

Her actions, her words and her dominion over Palmiter hung like a wraith over the court process, figuring in the narrative from nearly every witness. Her invisible presence will follow jurors into deliberations over the fate of the man she called her husband.

FBI poster for Madalina